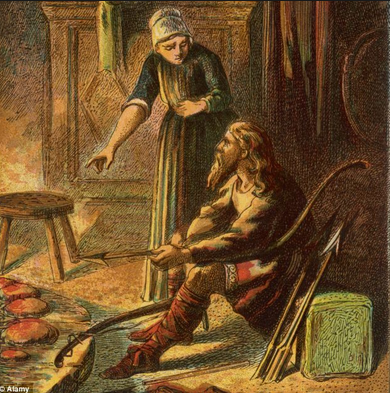

Those round things in the lower left are the hearthcakes. This supposed peasant woman is admonishing King Alfred for burning them, though they don’t look burnt to me. And why is she making peasant hearthcakes if she’s rich enough to own that fancy carved wooden thing behind her?

In the last post on everyday Anglo-Saxon bread, I talked about making bread on a bakestone or griddle on the fire. It is worth emphasizing again: for as much as eight hundred years, from the fifth century up to the thirteenth or fourteenth (and for centuries more in some areas of Britain), this would have been the familiar, everyday bread known to everyone in the kingdom. More affluent people ate leavened bread instead — or in addition. But everyone would have regarded this basic flat bread as familiar, completely normal bread. You did not need an oven to make it, and you didn’t leaven it; it was accessible to anyone, a quick, cheap, portable everyday bread.

Today we’ll look at an even more basic bread: hearthcakes or kichells cooked directly on the fire.

Before we get to the recipe, a little diversion on what to call this bread.

What do we call it?

It shows how far we have come from this easiest and most common of breads that we no longer even have a name for it. The closest equivalent is probably modern Scottish oatcakes, except that Anglo-Saxon bread would have contained some random combination of oats and barley, or of rye and wheat. And modern oatcakes usually have fat in them. And they’re smaller than Anglo-Saxon bread. Bannocks are also related, but at least in their modern form, they’re larger and thicker than Anglo-Saxon flat bread.

Jack Monroe’s bannocks (recipe here). Unlike most modern bannocks, these are the right size for early medieval hearthcakes. Even for these humble bannocks, Monroe directs the reader to use a cookie cutter or a glass to get them perfectly round; it’s as if modern cooks feel pressure to emulate the unwavering standardization of industrial processing.

So there’s really no modern term for the Anglo-Saxon variety. The word “cake” has come to mean a sweet, usually non-thin bready-caky thing, so the term “hearthcakes” is a bit misleading. “Ashcakes” has the same problem, plus they weren’t always cooked in ashes. “Flatbread” suggests something flatter than Anglo-Saxon bread.

I think we’re going to have to go with “hearthcakes” for these things, but it’s not really ideal.

What did the Anglo-Saxons call them? They seem to have had three words for them. The most common Old English term was cycel (pronounced “kichell,” related to the word “cook” and all its descendents like kitchen, cookies, cake, etc.). Basically a kichell (OE cycel) was the thing you made in your kitchen (OE cycene). The word cycel/kichel/kichell was used throughout the Middle Ages and up through the eighteenth century, as shown by nineteenth-century references to the cake known as a Gods-Kichell: “It was a good old custom for God-fathers and God-mothers, every time their God-children asked them blessing, to give them a Cake, which was a Gods-Kichell…”*

A second Old English term was bannuc, the ancestor of modern bannock. A third, early Anglo-Saxon term was sol, not to be confused with the sun or with other meanings of sol. The term sol used to be a bit controversial among earlier scholars; finally the evidence to prove that it meant “bread” has turned up; but that whole story is for another day. In any case, in the eighth century Bede wrote that the pagan Anglo-Saxons used to call February Solmonath (Sol-month): “Solmonath can be called the month of hearthcakes, which they used to offer to their gods in that month.”** Sadly we know nothing more about this practice.

So if you were an Anglo-Saxon of the sixth or seventh century, you probably said sol, but as the centuries wore on, you referred to it as a bannuc or, most likely, as a cycel.

One Latin term was placenta. This initially sounds a bit gruesome, but was derived from the Greek plakous, “flat cake,” from which the anatomical placenta was also named. A second term was torta (the ancestor of modern tart) or tortella (the ancestor of modern tortilla), though these could also be small rounds of leavened bread, similar to buns.

You can try making original Roman placenta here. By the Middle Ages, the term just meant any flat cake, not the fancier multi-layered kind that this intrepid blogger has made.

How do we make it?

Today we’ll discuss making kichells the most basic way: directly on the hearth. For this you need a fireplace or a campfire.

Start by repeating the procedure for hearthcakes baked on a griddle:

- First you decide on your level of poverty. Remember that by our standards most Anglo-Saxons were what we would deem “poor.” You will need one of the following:

if you are very poor:

pea and/or bean flour, which you should mix with oat flour in random proportion

if you are moderately poor:

oat flour, which you should mix with barley flour in random proportions

(this mixture is now known as dredge)

if you are a reasonably prosperous yeoman farmer:

wholemeal wheat flour, which you should mix with rye flour in random proportions

(this mixture is now known as maslin). Warning: if you use wheat flour alone, your reaction will be, ‘They ate this all the time? It’s rather dull, isn’t it?”

- Take a couple of handfuls of flour and put in a bowl. Add enough water to make a dough that is not too sticky. Ideally you have gathered this water from a source that is not downstream from someone with dysentery, though this too could be inauthentic. Do not add anything else. You do not need salt. You are not wealthy enough to afford fat or milk, and if you had some, you wouldn’t waste it on bread anyway.

- Knead the dough until it is well mixed. You don’t need a board for this. What are you, rich, that you have boards in your house? Just pass it back and forth between your hands, squishing it as you go.

- Let the fire die down to embers, maybe with a tongue or two of flame.

Thin hearthcakes on the embers.

Version A: The Thin Version:

- Form some of the kneaded dough into a flat roundish disc by patting it between your hands. It should be fairly thin, as thin or a bit thicker than a modern oatcake, at most a finger high.

- Lay your disc on the hot embers. When it looks as if it’s getting done and is a bit burny around the edges — these crispy bits will be extra nice — turn it over until the other side is equally done. Six or seven Lord’s Prayers’ worth of time should do it. (Remember, this was how they measured duration.) Don’t hurry over the prayers.

- When done, remove from fire. If any ashes remain on the bread, they can be dusted off easily — the bread will not be ashy.

Version B: The Thick, Bannock-like Version

- Form some of the kneaded dough into a disc two or three fingers thick. Put this on the embers once they have died down significantly. If they are too hot, the outside will cook while the inside stays doughy. You want the whole thing to cook through slowly.

- Turn when it seems as if it might be done on the bottom. Continue cooking until it’s probably done all through. This will require a good deal of praying, or gossiping, or other time-consuming activities. If you are sharpening your arrows against the Vikings, make sure you don’t get distracted and let the cakes burn. (Cf: King Alfred.)

This thicker hearthcake will give a softer, quite yummy texture.

These hearthcakes have some burnt bits which will provide some nice crispness when eaten.

Both of these are best when eaten hot. They should ideally be eaten with a spreadable new cheese: goat’s cheese or feta will be quite nice. Harder cheeses like Cheddar are less good with it. You want something spreadable and salty. A nice fresh butter would also be good.

Is this novel?

This bread form has been invented again and again in the history of breadmaking. The Scandinavians have held on to their own tradition in the form of flatbread, which is larger and flatter than cycels seem to have been. Bannocks, in Scotland and the north of England, are a fatter version, but remain stubbornly local. Chapatis and pita bread are similar but also flatter than a kichell. A tortilla is a similar, thinner concoction, made with cornmeal. Another tradition is that of the Australian damper, prized because it is so easy to prepare. Here is that authoritative source, Wikipedia, on damper:

‘Damper is a traditional Australian soda bread, historically prepared by swagmen, drovers, stockmen and other travellers. It consists of a wheat flour based bread, traditionally baked in the coals of a campfire or in a camp oven. Damper is an iconic Australian dish. It is also made in camping situations in New Zealand, and has been for many decades….The basic ingredients of damper were flour, water, and sometimes milk. Baking soda could be used for leavening. The damper was normally cooked in the ashes of the camp fire. The ashes were flattened and the damper was placed in there for ten minutes to cook. Following this, the damper was covered with ashes and cooked for another 20 to 30 minutes until the damper sounded hollow when tapped. Alternatively, the damper was cooked in a greased camp oven. Damper was eaten with dried or cooked meat or golden syrup, also known as “cocky’s joy”.

‘Damper is also a popular dish with Indigenous Australians. Aboriginal women had traditionally made bush bread from seasonal grains and nuts, which they cooked in the ashes of fires…’

The disappearance of kichells from mainstream Anglo-American cooking is the result of the wealth of the modern world, and of our neverending drive for fancier, lighter, fluffier, less filling breads, almost always dandied up with seeds or fats or sweeteners. You can see how far things have gone when even the most basic poor people’s breads now have milk and leavening, such as these Drop Scones and Scots Crumpets or Beremeal (barleyflour) Bannocks. The author of these recipes even writes, “Traditionally these bannocks would have been made without wheat flour or bicarbonate of soda; fortunately I have tasted the old way so you never have to”! But believe me, bread made the old way, with nice fresh flour and none of the fripperies, is all you need.

The proof is in the eating, and these were quite nice with goat cheese. The thicker kind have an enjoyable softness, but these are more portable. They also fill you up so that you could make an actual meal of a small amount, unlike modern fluffier bread. Some of these are wheat-and-rye, some are oat-and-barley. The oat-and-barley were lower-status in the Middle Ages, but frankly we think they taste better, with a nice hint of crunchiness.

Modern bread still holds its own at breakfast in the form of toast, but at lunch it is largely a vehicle for sandwich fillings, and it appears at dinners as a deliberately unfilling stopgap before the main course. Bread has become a vestigial food. To make these hearty, basic, honest kichells is to eat the way people ate when bread was the staff of life. They return us to the vast sweep of centuries when people literally could not have lived without them.

________________________________________________________________________________

A bonus sobering bread text from the later Middle Ages, on the “Ember Days.” The Embers Days are twelve days appointed for prayer and fasting, three days in each season, based on the date of Easter and other factors. In the Middle Ages, bread was exempt from fasting; in other words, if you were fasting you could still eat bread. Incidentally the interpretation of “Ember Days” quoted below is no longer accepted. Translation follows.

Then 3e schull know þat þes dayes byn callet Ymbryng-dayes, for, as opynion of summe ys, þay byn callet Ymbryng-dayes for encheson þat our old faders wolden ete þes dayes kakes bakyn yn þe ymbres and was callyt ‘panis subciner[ic]ius,’ ‘brede bakyn yndyr þe askes,’ and to askes schuld turne þay wyst neuer when; so þat etyng of þys bred, þay reducet to mynde how þay were but askes…

Then you shall know that that these days are called Ember Days, for, as the opinion of some is, they are called Ember Days because our fathers would eat these days’ cakes baked in the embers and they were called ‘panis subciner[ic]ius,’ ‘bread baked under the ashes,’ and they [the fathers] never knew when they [themselves] should turn to ashes; so that in the eating of this bread, they recalled to mind how they themselves were but ashes… (Mirk’s Festial, ed. T. Erbe, EETS es 96 (London, 1905), p. 254)

*Giles Jacob, The Law Dictionary, rev. T. E. Tomlin, 6 vols. (New York, 1811), vol. IV, s.v. “Kichell.”

**”Solmonath potest dici mensis placentarum quas in eo diis suis offerebant.” Bede, De temporum ratione, c. 15 (Bedae Opera de Temporibus, ed. C. W. Jones (Cambridge, Mass, 1943), pp. 211-12).

— MB

We are on Twitter! Follow us at @earlybread.

Completely absorbing on a rainy morning before eating my own dry bread and goat cheese

LikeLiked by 1 person

To my peeps (Ashkenazi Jews) a kichel is a small egg cookie(pl. kichlach). Stella D’Oro used to make a variety – I think there were even sugar-free ones made with saccharine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aha! A long-lost cousin of the Anglo-Saxon kichell! The online Merriam-Webster says: “Yiddish kikhel small cake, diminutive of kukhen cake, from Old High German kuocho.” Good old Indo-European cooking/cake terminology.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have been trying to share this on Facebook which says repeatedly that it can’t find the URL. Is there a problem on the blog’s end?

LikeLike

Well, that is weird. You can always get to the website at earlybread.wordpress.com, or I guess formally that would be https://earlybread.wordpress.com/. I wish I were as adept at the internet as I am at eating bread… Thank you for pasting and sharing if you can manage it!

LikeLike

I used the main URL as you posted with directions on finding the specific blog. The problem seems to be with using the Facebook icon at the bottom of the post. It still didn’t work and said URL not found.

LikeLike

Oh dear, I’m sorry. The problem is undoubtedly that when I look at the post, from the “author’s view,” it doesn’t show me any Facebook icon at all. I’ll try to figure this out.

LikeLike

You have a wonderful writing style, personal, informative and amusing – I really enjoyed finding this in my inbox and I’m looking forward to trying the recipe. I might try leaving some leftover dough to stand for a couple of days, or mix it with the next batch to see how long it takes to develop a sourdough leavening and flavour.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And I think then the experiment would be to see what happens when you try to cook a leavened or semi-leavened sourdoughed hearthcake on the hearth or the griddle. Does it rise so much that it’s hard to cook it all through? Or does it fail to rise when cooked so quickly, and so putting in the leavening doesn’t make much difference? Since only very rich Anglo-Saxons had ovens — oven-owning would have been much like Ferrari-owning now — a regular person wouldn’t have an oven to bake it in, or even know anyone with an oven. Even in the later, rich Middle Ages, a whole town would only have one, communal, oven. (It was big and in the open, and people also slept on it at night in cold weather.) Anyway, do report back if you have any findings! Also, isn’t it interesting that as moderns whose definition of bread is basically “leavened bread,” we’re always tending to add leavening?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve cooked home sourdough flatbreads similar to pitta bread on my griddle on the gas stove. Provided the heat is moderate they cook as usual. If I made them thicker I’d drop the heat more and perhaps put a bowl over the griddle to trap heat and moisture to stop the tops drying out… and then you’re halfway to an oven 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

You have anticipated Version 3! Which is to invert a vessel over the hearthcakes and make a homemade oven. Great minds… think like the Anglo-Saxons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Susan Macdonald's Blog and commented:

I found this fascinating, and I’m going to be following all the links and looking for other blogs by the same writer.

LikeLike

Re King Alfred burning his cakes – there’s a fungus named after them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on pmayhew53.

LikeLike

Interesting article, but I don’t like how it says ‘kichel’, to ‘cook’, ‘cake’, ‘cookie’ and ‘kitchen’ are all related to each other — ‘cook’ and ‘kitchen’ are from Latin coquere and coquina, which go back to PIE *pekw- (through *kwekw- in pre-Latin, by assimilation of the first consonant to the last), found in Sanskrit pac- ‘to cook, ripen’, Greek pepōn ‘ripe’ and Russian peč’ ‘to bake’. ‘Cake’ and ‘kichel’ and ‘cookie’ are from Germanic words of the form of *kak- and *kōk- (and possibly *kuk-), which would correspond to words in Latin and Greek of the forms *gog-, *gōg-, which do not exist in those languages but similar forms are found in Romanian gogoașă (“doughnut”) and gogă (“walnut, nut”) and Lithuanian gúoge (“head of cabbage”) (see https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/cake). Thus the article conflates words of quite different origin because of their superficial similarity.

LikeLike

Will strive to be clearer in the future!

LikeLike

This is great. Thank you.

LikeLike

Welsh grandparents used a bakestone on their kitchen range to make flatbread and Welsh cakes.

LikeLike